Cambodian military bases can serve as tools to influence Beijing.

Updated: Wed, 11/01/23 at 12:49pm

benjamin blanding

Hyderabad: The 2019 agreement between China and Cambodia on the Reem base recently sparked a wave of attention-grabbing publications and commentary. The agreement provides for the opening of facilities and the stationing of Chinese troops at the Cambodian military naval base. For many observers, Beijing has thus further tightened its grip on Southeast Asia, along the now-famous “String of Pearls” (a reference to Chinese strongholds along major routes for energy supplies from the Middle East).

How can this revival of interest be explained, nearly three years after the initial disclosure in the Wall Street Journal and the ongoing publication of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (CSIS-AMTI), although no concrete (in the military, any case) agreement has yet landed ?

Rising tensions in the South China Sea, lack of significant progress on a code of conduct in the South China Sea (Manila Declaration, 1992), which China and other littoral states have been working on for nearly three decades, and Beijing’s aggressive diplomacy in the Covid era have arguably helped raise concerns about China’s role in the region. Areas of concern for any new initiatives. What is it in practice?

A storm in a glass of water?

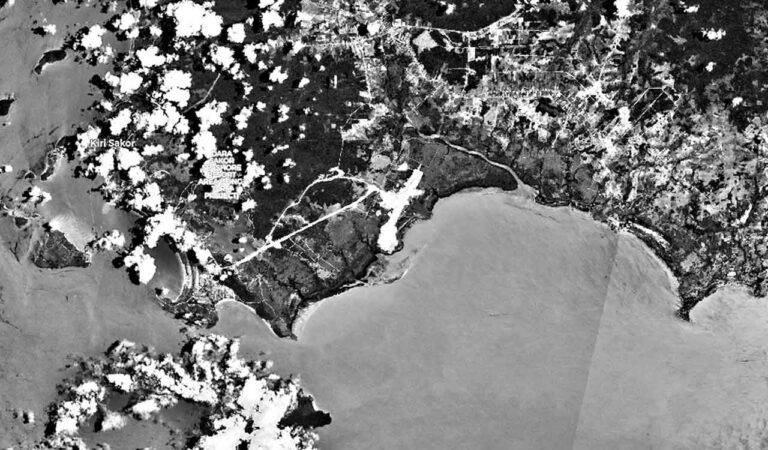

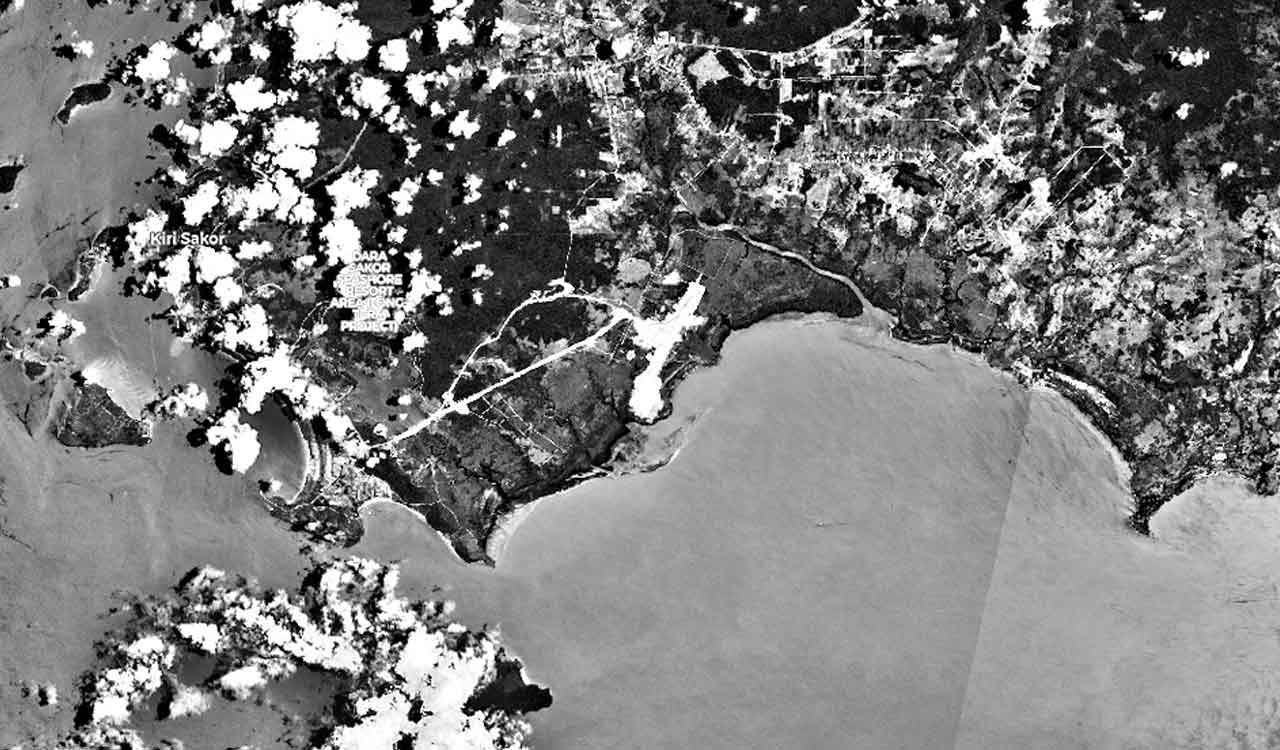

The facilities at the Ream base are spartan, limited to a dock and a set of logistical and administrative buildings spread over nearly 77 hectares, which may indicate references to China’s “secret base in Cambodia.”

This impression is reinforced by the presence of a seven-meter-deep seabed, which only allows vessels of medium size (up to 1,000 tons) to dock, such as patrol boats. For the Chinese navy, the a priori strategic benefits are small, and none of its major forces can benefit from existing facilities. For what purpose, even though it already has a strong naval air base in the Spratly and Paracel islands?

However, a number of factors have raised questions, notably the secretive nature and terms of the agreement, which may reflect Beijing’s influence over Cambodia’s security establishment and the stranglehold that Chinese networks have on the country’s economy, especially in Phnom Penh and on the coast, especially in the West. Hanoukville area.

hide another transaction

Formally, the agreement aims to modernize the base’s port facilities with technical and financial support from China to allow the reception of larger ships on site and facilitate the Cambodian Navy’s ability to carry out its security missions. Shipping in the Gulf of Thailand.

However, the agreement is not limited to infrastructure investment considerations, and it should be remembered that US- and Vietnamese-funded buildings were destroyed and demolished before construction could begin – a precedent that has strained relations between Phnom Penh and Vietnam. washington.

Again, the terms of that agreement were never made public, but we now know that, in addition to granting China a lease on half of the base, for an initial period of 30 years, renewable by implied renewal, to build facilities, dock ships, and store weapons and ammunition.

It is surprising to find Chinese military personnel patrolling the perimeter of the base armed and wearing Cambodian uniforms or civilian clothes. Chinese soldiers will also hold Cambodian passports.

exclusive link

Furthermore, it is no secret that extremely strong security ties have united China and Cambodia since the days of the Khmer Rouge. At that time, at a time when the Sino-Soviet ideology was clashing, China did provide strong support to the Khmer Rouge regime against the invasion of Vietnam.

Since then, China has become Cambodia’s main arms supplier, and the pace has only accelerated in recent years, with donations and sales at cost, about $240 million over the past decade. Quantities include logistical and armored vehicles, artillery, helicopters, air defense systems, uniforms, small arms and ammunition.

The situation is even more dire for the Royal Navy, where all 15 active patrol boats were donated by China in 2005 and 2007 – so Phnom Penh must obtain all spare parts from China, which could seriously challenge Cambodian sovereignty.

In the field of officer training, China has made great contributions to the creation of military academies with curricula designed by the Chinese Ministry of Defense and taught mainly by Chinese personnel. The training also includes a mandatory six-month internship in China.

This comprehensive security support was accompanied by political support for Prime Minister Hun Sen (in office since 1998), which prompted the latter to systematically support Beijing’s interests in 2012 and 2022, especially as ASEAN chair, or through the handover of Uyghur to the Beijing authorities.

The agreement with Cambodia is China’s second foreign facility after Djibouti, apart from facilities in the South China Sea. Once equipped, the Yunlang base will be able to accommodate ships weighing up to 5,000 tons, including most frigates and frigates, and even some Chinese Navy destroyers.

Indonesia’s Natuna Islands are equidistant from Ream and Chinese installations on Fiery Cross Reef (Spratly Islands), and it goes without saying that the possibility of the Chinese Navy supplying both sides with the other part of the archipelago can only lead to concerns about its security systems and Pressure on resources increases. This is all the more so since there have been many conflicts in its exclusive economic zone, which has prompted it to beef up its systems in recent years.

Other ASEAN countries along the South China Sea (in addition to Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia) are also concerned about the Yunnan facility. Cambodia’s neighbor Vietnam, in particular, has had multiple border clashes with China, not to mention frequent clashes between Vietnamese fishing boats and the Chinese coast guard.

Media gimmicks, backhand technology to intimidate Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia at the same time, cheap strengthening of its strategic apparatus, a show of force against ASEAN… It must be admitted that for China, the deal with Cambodia is becoming more and more akin to a game of Go Main line: Beijing is demonstrating sweeping activism to advance its interests in the region.

Technology in Phnom Penh

As we have seen, the seemingly modest agreement between China and Cambodia to grant a permanent facility at the Reem base is actually very important from the perspective of China’s strategy in the region.

With Cambodia, however, one should not jump to the conclusion that the kingdom is loyal to China. King Norodom Sihanouk (reigned from 1941 to 1955, then from 1993 to 2004) knew better than anyone in his time how to widen the reversal of the alliance, with France, then the United States, then Russia and China engage. A cunning man, Prime Minister Hun Sen, has wielded real power for 37 years and himself knows how to navigate from one ally to the next to stay in power.

While Cambodia’s main trading partners are the European Union and the United States, the primary political and security partner is clearly China. However, this should perhaps be seen as a sign that three of Hun Sen’s sons completed their military studies, not in Beijing but in the United States (Hun Manet thus at West Point, Hun Manith at the George C Marshall Center for European Security Studies, Hun Many at the National Defense University) – proof that China does not yet control all levers of power in the country. (theconversation.com)